English & Literary Studies

The effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students; A case study of selected Tertiary Institutions in Owerri zone

Published

4 years agoon

ABSTRACT

This research work is on “The Effects of Bilingualism on the English of Tertiary Students”. The term bilingualism is the use of two languages by an individual or a community. That is the existence of two languages in the repertoire of an individual or a speech community. An important feature of bilingualism is that it is a consequence of language in contact which deals with the direct or indirect influence of one language on the other. The term ‘bilingual’ is used in describing people who know two distinct languages. Five research questions were used to investigate the effects of Bilingualism on the English of tertiary students. A total of three hundred (300) students from two tertiary institutions were used to carry out the investigation. Fifty (50) percent and above is regarded as a pass mark proving the effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students. The selected tertiary institutions are run by the state and federal governments. The interpretation of the data proved that bilingualism has positive (benefits) and negative effects on the English of tertiary students which includes enhancing and enriching the students’ language experiences, offering insights and opportunities for developing cognitive skills, enhancing ability to interact in the two languages, transfer concepts from one language to the other and a means of cultural transmission. However, the negative effects or consequences include: code-mixing, code-switching, mother-tongue (L1) interference, borrowing etc among other effects. Based on these interpretations or findings, recommendations such as encouraging parents to maintain bilingualism at home, and encouraging their children and wards to use both languages, language teachers’ emphasis on areas of difficulty and interference, more emphasis to be made by textbook writers, syllabus designers, curriculum planners, provision of instructional materials and financial assistance by the government were made to enhance proficiency.

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

- BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

LANGUAGE

One striking characteristic of a human being and something that distinguishes him from any other animal is the ability to use language in its most dynamic form namely speech. Every human society possesses a language, which is physiologically expressed in the vocal system and used in exchanging views about the universe. Anyanwu (2002:24, 25) posits that no human being is born speaking a language meaning that language is not inherited. However, every normal human person is born with the capacity to master the language spoken in his immediate environment and he achieves this complex task over time starting from the moment of his birth such that by the time he has attained six years and above he has become a user of that language. There are so many definitions of language by linguists in a bid to portray the importance of language in human existence. Akindele and Adegbite (1991:1) opine that language is characterized by a

set of vocal sounds which can be decoded. These are produced by the human organs of speech-lips, tongue, larynx etc. The vocal sounds produced by the vocal organs are used in various systematic and rule-governed combinations. Language is thus a human phenomenon that has form which can be described in terms of the unit of sounds (phonemes), words, morphemes, phrases, sentences and paragraph or discourse. Form refers to the means by which sounds are connected with meaning in language.

‘Language is the source of human life and power’ Fromkin et al. (2007:3). Human language is unique in the sense that it has its own structure, its system of organizing its component units into meaningful patterns.

Quirk (1971:42) defines language in the abstract as our facility to talk to each other; it is the faculty of speech which all human beings hold in common.

Fromkin and Rodman (1978:22) gave a definition that encapsulates all the divergent views of language. Thus “language is a conventional system of habitual vocal behaviour by which members of a community communicate with each other”. This definition suggests about five characteristics of language which include that: language is conventional, systematic, habitual, a vocal behaviour and a means of communication.

Language is also characterized by a set of arbitrary symbols that is, there is no one to one correspondence between the object and symbol, which stand for it.

Yule (1996:25) identified the unique properties of human language as follows: Displacement, Arbitrariness, Creativity, Discreetness, Duality and Cultural Transmission.

In summary, it can be described as system of sounds or vocal symbols by which human beings communicate experience. It is specie specific to man, that is, it is a special characteristic of human beings. Man uses language to communicate his individual thoughts, inner feelings and personal psychological experiences.

Language is used to establish social relationship. For instance, when you use language to greet, its function is phatic rather than informative. Language does not exist in a vacuum. It is always contextualized meaning that it is situated within a socio-cultural setting or community. There is a necessary connection between language and society. It is a means of expressing a society’s tradition and culture. So language exists as an aspect of culture. Yule (1996:6) also identifies two major functions of language as: Interactional and Transactional. Interactional Function of Language according to Yule is its use by humans to interact with each other socially or emotionally, to express friendliness or hostility, pleasure or pain etc. While Transactional function is its use to communicate knowledge, skills and information. Wallwork (1974) in Nwachukwu et al (2007:10) also summarized other specific uses of language as follows: Phatic communion, ie. Language used to establish social relationship, for ceremonial purposes, as instrument of action, for Record keeping, for passing on facts and information for influencing people, enabling self-expression and embodying and enabling thought.

1.2.1 THE STATUS/ROLE OF ENGLISH IN NIGERIA

English language is retained in Nigeria today because it is the language for expressing the institutions the colonizers left behind. Thus the business of education, technology, administration, judiciary and mass media proceed in the English language. English language occupies a dual status in Nigeria namely second language and Lingua Franca: Although there is no official statement on the status of English as a lingua franca in Nigeria, the language plays the role from the perspective of usage. Nwachukwu et al. (2007:74)

The term second language is generally used to describe any language whose acquisition starts after early childhood. For most Nigerians, English is learnt after the acquisition of native language. Encyclopedia Britannica (2007) describes lingua franca “as language used as a means of communication between persons having no other language in common”. In the multi-lingual Nigerian situation, English plays the additional functions of a common means of communication amongst members of different language groups.

Although there is no explicit declaration assigning lingua Franca status to English in Nigeria. It is the language of widest/most common interaction among all the ethnic groups in Nigeria. The functions of English in Nigeria are looked at from the perspective of second language and lingua franca.

English as a Second Language In Nigeria

English is seen as the language of National stability. This is because Nigeria is a multi-lingual country with about four hundred and fifty languages Osuafor (2002:15).

English and Education

Nwachukwu (2002:15) opines that English has remained the primary language of education right from the colonial era. The language provisions of the National policy on education (2004) clearly defines the functions of English in primary education in Nigeria thus:

”The medium of instruction in the primary school shall be the language of the environment for the first three years. During this period, English shall be taught as a subject”.

According to this National Policy on Education, the mother tongue is the medium of instruction in lower primary while English is studied as a school subject at this stage. Thereafter, English remains the medium of instruction and compulsory school subject until the end of secondary education. All textbooks except those on the indigenous languages and French are written in English. It is a partial medium of instruction in the teaching of even the indigenous languages and French. Examinations in all subjects (except the indigenous languages) are written in English and certificates from primary school to tertiary level are also written in English. It is the only subject that is compulsory at all examinations for admission into secondary schools and tertiary education. Competence in English (spoken and written) is an index of good education in Nigeria. It is as a result of these criteria that the minimum pass grade for admission at the tertiary level in Nigeria is a credit pass. English is also a compulsory subject in tertiary education and it is studied with a variety of course titles in the universities, polytechnics and colleges of education as either “use of English” or “General English”, or “Communication in English”. A minimum of a pass grade is mandatory for graduation from tertiary education irrespective of area of discipline. The English language is for now an indispensable language in the Nigerian educational system.

English and Government

English is the primary language of officialdom in Nigeria. Although there is no rule that forbids the use of indigenous languages in official transactions, English has remained the language of official documentation and general official transactions. Ogu (1992:93) states that “…. The stand of government policy is that English is the national language in Nigeria and to be used in political administration and for education purposes”. All official correspondence in the civil service are conveyed in English. Section 51 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria states that:

“The business of the National Assembly shall be conducted in English, Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba when adequate arrangements have been made”

The business of the national Assembly is now conducted in English and this suggests that “adequate arrangements” for the use of Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba are yet to be made. Similarly, the language provisions of the state House of Assembly favour the use of English. Ogu (1992:93) quotes section 91 of the Nigerian Constitution which states that:

The House of Assembly shall be conducted in English but the House in addition to English, conduct the business of the House in one or more other languages spoken in the state as the House may by resolution approve”.

The language of the judiciary, which is an important arm of government, is English. From the Customary Court to the Supreme Court, the language of Law in Nigeria is English and this is evidenced in various ways. For instance, Laws are written in English and the court uses interpreters in situations where any party in court does not understand English. Again, legal proceedings are in English even in situations where the presiding magistrate or judge speaks and understands the language of the parties before him in the court..

The primary language of politics in Nigeria is English. All national campaigns and election programmes are conducted in English. Even in the state level where people have a common language, the language of politics is still English or Pidgin English particularly in Southern Nigeria.

Similarly, the official language of the armed forces (military), the paramilitary and the police in Nigeria is English though interpersonal interactions may be in the indigenous languages.

The mass media, which is another important arm of the government, has English as its primary language. Information is power and the language of mass media in a country is significant. The national news, (Radio and Television) is read in English and National news in the major Nigerian language is available only on a few stations.

The major Newspapers in Nigeria are produced in English and only a few, particularly propaganda and comedy are produced in Hausa and Yoruba in particular. Most advertisements that are of national relevance are in English.

English as Lingua Franca

English is a non-native language in Nigeria but it functions as lingua franca (common language) in the multilingual and multi-cultural Nigerian settings. English is the language of widest communication amongst Nigerians in the 21st century. In discussing the usefulness of English as a unifying force in Nigeria, Jowitt (1991:23) cites Adebisi Afolayan who states that:

“It is unrealistic for anybody in Nigeria today to think that National Unity can be forged in the country without recourse to the utilization of the English language ….”

Furthermore, the fact that it is now functioning as the language of nationalism cannot be denied”.

Ogu (1992:94) in his discussion of the matter states that:

“It has since become clear that this language (English) which used to be a taunting reminder of our colonial past has no immediate connection with the political and economic supremacy of the past.

Gradually, but significantly, English is getting into every home. This gradual development is a response to a change over which nobody can exercise control, a change from the strong village ties of the past to the demands of modernity”

Ogu (1992:94) further argues that English is no longer a foreign language in Nigeria. It has been adopted and appropriated to Nigeria and is used as the language of education and made to fulfill all the roles normally reserved for mother tongue.

As a lingua Franca (common language) English is the primary language of social interaction amongst different ethnic and language groups in Nigeria. It is estimated that there are more than 400 languages in Nigeria. In this multi-lingual and multi-ethnic setting, English is readily the means of communication particularly among the educated class. The uneducated also find a form of English ranging from pidgin to “ Broken” English, a convenient option in situations where the different language groups are unable to communicate in any Nigerian language. It is indeed a trade language for business transactions whenever there is need for a common means of communication. Even some Nigerians from the same language group but different dialects rely on English for mutual communication, especially in Southern Nigeria.

English has even become a common language among some Nigerian children who are resident in Nigeria but speak no other language except English. Pear group interaction is often in English, especially in cosmopolitan cities where different languages are spoken. Christian religious programmes including sermons and tracts depend mainly on English particularly in the urban areas. It is a normal practice with some Christian denominations in Nigeria that sermons are preached in English and interpreters used even in situations where the entire congregation including the preacher understands the language of the interpreter.

In conclusion, it is clear that in the 21st century, English has remained an Indispensable second language that also functions as a lingua franca in Nigeria. Competence in the language is therefore a basic necessity for every Nigerian who desires to be relevant in the socio-political and economic activities in the country.

- LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

Language Acquisition is defined by Wilkins (1974) in Nwachukwu et al. (2007:28) as the process where a language is acquired as a result of natural and largely random exposure to language. From the first day of his existence, the child is bombarded with language by those around him especially his mother and other members of his family. During the first twelve months or thereabout, the child is more or less an observer but unknown to many, a keen listener. It is obvious that he has been listening and practicing all along when from the blues, as it may seem, he utters a meaningful expression, such as ‘mama’. In the next four years, the child acquires his native language through corrections he receives for his mistakes. For instance, the child discovers that though the plural of ‘pan’ is ‘pans’, the plural of ‘man’ is not ‘mans’ but ‘men’.

There are various ways in language acquisition in which the learner gets a feedback. The adults present might simply tell the child he has made mistake and correct him or may just reformulate the child’s utterance in a more grammatical form.

Wilkins (1974:30) posits that the feedback provided by other people does more than simply inform the child whether or not his message is correctly formed. It also demonstrates to him that his language has an effect on the behaviour of others. In essence, the child becomes aware of the regulatory function of language. This motivates him a great deal in learning the language. The rate and quality of learning in children will not be identical since they have different intellectual gifts. Absence of physiological and psychological handicap fosters the process of language acquisition.

1.3 THE NOTION OF BILINGUALISM

The term Bilingualism can be defined as the use of two languages by an individual or community. That is the existence of two languages in the repertoire of an individual or a speech community (Akindele and Adegbite (1999:28). The two languages exist side by side and are used by the individual or community. It is the native – like control of two languages.

Bilingualism is also described as the ability of an individual to produce update meaningful utterances in the other language. An important feature of Bilingualism is that it is a consequence of language in contact, which deals with the direct or indirect influence of one language on the other (Mackey, 1968) in Akindele and Adegbite (1999:28).

Osuafor (2002:196) stated that in Nigeria, there is contact between the English language and the Vernacular of the different ethnicities. And the result is the presence of people who are users of both their vernaculars (L1) and the English language (L2) in the country. Thus, there are Igbo – English, Yoruba – English, Hausa -English bilinguals and so on.

Each of the two languages in Bilingualism has its own distinct phonological, lexical, grammatical and discourse rules. Each therefore forms a code of communication in the community or individual who uses it. Examples of Bilingual speech communities are Canada where English and French are considered very important to the life of the people; Nigeria where several bilingual speech communities exist for example: Hausa/kanuri bilingual community and in Britain where some communities are bilingual e.g. Wales where they speak Welsh and English.

1.4 THE ORIGIN/CAUSES OF BILINGUALISM

The genesis of bilingualism could be traced to the following factors namely; colonialism, conquest, trade and commerce, annexation and border line areas. Akindele and Adegbite (1999:28)

1.4.1 MIGRATION AND WARS OF CONQUEST

The situation of conquest arises from large group expansion when a powerful nation embarks on a particular war in order to be able to control the politics of a weaker nation. This was the situation with a country like USA, which was dominated by the Indians originally but was conquered and ruled by the British who later introduced the English language as well as its culture to that society. In essence, the community became bilingual. The same factor was also responsible for the Australian State.

It is also possible for small members of a group to migrate to a larger community. For example, the 19th century and 20th century European and Chinese migration to the U.S.A Akindele & Adegbite (1999:29).

Trade and Commerce

An individual or community who attempts to trade with another individual or community also results in bilingualism. In bilingual trade and commerce activities, it is not only goods that are exchanged but also the languages and cultures of those involved. This reason accounts for why many Nigerians are able to speak their mother tongues in addition to other indigenous languages.

1.4.2 COLONIALISM

One of the major sources of bilingualism is colonialism. This could be in two forms. The first form involves the process of ruling the indigenes of a particular state through their traditional rulers. In this process, the language and culture of the colonialist are introduced through the process of education into the social, economic and political life of the nation involved. It is through this process that many African states, particularly those ones occupying the Anglo-region, for example, Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya became bilingual in English and their mother tongues.

This is the situation with French. French assimilated Francophone African nations who were made to believe that they were part and parcel of France. In such situation, there was less resistance to the introduction of French language and culture in all the countries colonized by the French. Such countries became bilingual in French and their indigenous languages.

1.4.3 BORDER CONTACT

This is another clause of Bilingualism in which a community shares the border of two different countries. For instance, the occupants of Idi-Iroko, a community which shares the boundaries of Nigeria and Benin Republic are bilingual simply because they interact with the Beninous who speak French and the Lagosians who speak Yoruba. The inhabitants of this town speak Yoruba and French. These people are also bicultural in experience. The sharing of common markets, religious centers and other social, cultural and religious activities by inhabitants of border towns also cause bilingualism.

1.4.4 ANNEXATION

This is another cause of bilingualism. The annexation of a community to another one results in bilingualism. Annexation refers to the process whereby a community forcefully acquires another community. The annexed community is made a part of the acquiring community and members of the two communities can acquire each other’s language. Annexation also is a type of imperialism, however, it is different because colonization involves crossing the ocean.

1.4.5 EDUCATION AND CULTURE

A further cause of bilingualism is Education and Culture. Throughout history, particular languages and cultures have dominated the lives of people across the globe. In the Roman Empire for instance, Greek was the language of Education and Culture. Almost all educated Romans were educated in Greek and Latin which were the languages of Philosophy, medicine, Rhetoric and Literature.

With the spread of Christianity, Latin became the dominant language of Culture. English is the usual international language of science and technology. Thus in all these periods, many educated people have been bilingual or multi-bilingual in their native language and in the language that was culturally prominent at the time.

1.4.6 FEDERATION OR AMALGAMATION

Bilingualism can result from federation or amalgamation of diverse ethnic groups or nationalities for example, Nigeria and Cameroon. This type of federation is often forced and after independence, some of the groups or states may attempt secession.

For instance:

- Biafra from Nigeria

- Katanga from Zaire

- Bangladesh form Pakistan.

1.4.7 NATIONALISM AND POLITICAL FEDERALISM

This is another cause of bilingualism. Nationalism had a great impact on the spread of national languages in preference to regional languages. There is a conscious process on the part of the Government that Igbo, Hausa and the Yoruba (WAZOBIA) are used as the major official languages. If for instance, Government Policy forbids the use of English as national language in schools, and public life, then bilingualism will be short-lived.

1.5 TYPES OF BILINGUALISM

Akindele and Adegbite (1999:31) identified three factors or types of Bilingualism. They are

- User

- Chronology/time

- Learning situation and

- Purpose

User: In terms of the user, there are two types of bilingualism, namely: Societal and Individual bilingualism. Societal bilingualism can be defined as a situation whereby two different languages exist and function independently of other languages within the society concerned. The two languages dominate the socio-linguistic repertoire of the speech community. The languages are assigned significant roles by the society. They function as a means of communication in that society.

Societal bilingualism is otherwise referred to as National (or Government) bilingualism. That is the use within a single polity of more than one language (Stewart, 1968). This arises as a result of the eventual elimination, by decree or education of all but one language, which is to remain as the national language. It is also due to the recognition and preservation of important languages within the national territory supplemented by the adoption of one or more languages to serve for official purposes and for communication across language boundaries within the nation, as in the case of English language, Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo.

A very significant factor in describing cases of national or societal bilingualism is the specification of the functions of each of the linguistic codes within the communities. The languages involved in societal bilingualism must function as legally appropriate for all politically and culturally representative purposes on a nationwide basis. The official function of the languages is specified constitutionally.

Individual bilingualism refers to an individual whose repertoire is dominated by two distinct codes of communication. Such an individual who may be a member of a bilingual community or multi-lingual community has the ability to acquire grammatical and communicative competence in one of the languages and lack competence in the other. An important factor about a bilingual person is his ability to sustain two different codes of communication.

Bilingual types identified in terms of ‘Time’ are simultaneous and ‘sequential’ or consecutive bilingualism. In simultaneous bilingualism two languages are learnt at the same time, usually at an early age whereas in sequential bilingualism, the languages are learnt at different times.

In sequential bilingualism, the first language or mother tongue is acquired at birth while the second language is acquired later. Bilingualism acquired at a later stage is referred to as ‘late’ or ‘adult’ bilingualism.

In terms of ‘Learning situation’, bilingualism can be acquired at school or out of school. Bilingualism acquired out of school is known as “informal bilingualism’. In Nigeria, societal bilingualism is achieved formally and sequentially since a child normally has a mother tongue acquired at home and English learnt later at school.

In terms of ‘Purpose’, bilingualism is identified when the two languages are used for the same functions and or the same amount of functions, which is very rare, then we have a situation of ‘Balanced’ bilingualism or ‘Ambilingualism’. In that event each of the two languages is a mother tongue. But when the two languages are used for different functions and/or different amounts of functions, we have a situation of ‘Non-balanced’ bilingualism. In this case, one of the languages is primary and is used for everyday activities while the other is secondary and is used for formal or special activities.

1.6 THE EXTENT OF BILINGUALISM

The extent of bilingualism can be described in respect of the following degrees of individual bilingualism: coordinate bilingualism, subordinate bilingualism and incipient bilingualism. Akindele and Adegbite (1999:32).

1.6.1 COORDINATE BILINGUALISM

A coordinate Bilingual is a person who is able to speak two different languages and understand them well. Such a person will have acquired communicative competence in the two languages whereby he will understand the roles of each of the languages perfectly well and be able to communicate effectively with them in any situation. Such a person will be able to do so without giving room to any suspicion that he or she is more competent in one of the languages than the other. This means that the bilingual person is able to separate effectively well the codes of each of the languages being used. This group of individuals has a near native-like competence in the two languages.

Coordinate bilingualism differs from compound bilingualism in that in compound bilingualism, the two codes are available for one semantic reality, they both serve principally to express the same background and culture (e.g. English and French in Canada). This type of bilingualism occurs mostly when both languages are learned at about the same time under similar circumstances and used in the same situation e.g. at home or at school.

In the coordinate bilingual, the two languages function independently and may express two distinct backgrounds and ways of life, the native and the non-native culture (e.g. Igbo and English in Nigeria). There is normally a single or mixed store for both languages. Such a bilingual will thus be able to have the same reference for two words, one in each language.

1.6.2 SUBORDINATE BILINGUALISM

A subordinate bilingual is an individual who is fluent in one language but is not able to speak fluently in the other. For instance, someone may be good in his mother tongue both in spoken and written form but not good in English.

A subordinate bilingual is usually competent in the grammar as well as in the communication process of one language. Such a person can be equated with a native speaker of the language in which he/she is fluent. On the other hand, he/she may be fluent in the spoken form of the two languages but less competent in the grammar of one of them. A subordinate bilingual is usually unable to speak one of the two languages the way a native speaker does. In the speech of such an individual, interference is readily discernable even though he can still be understood. Examples of subordinate bilinguals can be found in the Nigerian educational system varying from the nursery to the university level whereby certain individuals are very fluent in the (mother tongue) MT but are deficient in the second language.

1.6.3 INCIPIENT BILINGUALISM

An incipient bilingual is an individual who speaks one of the two languages existing in his speech community well but only understands the second language partially. Such an individual is very competent in one of the two languages, most often the mother tongue. For example, there are the semi-literate speakers of Igbo, Yoruba and Hausa who speak their indigenous languages, but cannot speak or understand English well. Examples are found in Nigeria among petty traders, touts etc. This category of Bilingual may be unable to produce any correct sentence or utterance in the second language but they still indicate some understanding.

1.7 THE OUTCOME OF BILINGUALISM

The outcome of bilingualism is observed in two respects namely stable bilingualism and transitional bilingualism.

Stable Bilingualism: This is described as a situation whereby two languages are maintained for a lengthy period of time. There must be good reasons for a group to remain bilingual. As long as there are different monolingual communities in a nation and there is the likelihood of contact between them, this results in bilingualism. (Mackey, (1968:555). Canada, Switzerland, Ghana and Nigeria are destined to have long term bilingualism, even though only a small percentage may be bilingual.

These countries are made up of separate monolingual communities with a small portion of the population serving as bilingual contact between the groups. The language of contact is usually the dominant/prestige language. English and French for Canadians and English for Nigeria.

Transitional Bilingualism: This takes place when a bilingual group reverts to mono-lingualism (for example: German and Turkish to German), when foreign influence diminishes. A self-sufficient bilingual community has no reason to remain bilingual since a closed community in which everyone is fluent in two languages could get along just as well with one language. (Akindele and Adegbite, 1999:34).

Transitional Bilingualism has three forms, which includes – the maintenance of the group’s original language may lead to the disappearance of the L2. Non-maintenance of the L1 may result in language shift or displacement of the L1. For example, Egyptian to Arabic. Also, a new language may result through the processes of pidginization and creolization as can be seen in Haiti, Jamaica and New Melanesia. (Akindele and Adegbite (1999:34)

1.8 THE EFFECTS OF BILINGUALISM ON THE ENGLISH OF TERTIARY STUDENTS

Bilingualism has both positive and negative effects on the English of tertiary students. The positive effects, which can also be called Benefits of bilingualism, are as follows

1.8.1 THE BENEFITS/POSITIVE EFFECTS OF BILINGUALISM

The effects of being bilingual are positive in terms of language development as a whole including the first language. When learning two languages at the same time, the learner becomes aware of language itself, having two or more words for each object, idea or concept will expand rather than contract the mind.

There will be transfer in thinking from one language to another that is if a child is taught Mathematical multiplication and division in one language. Those skills do not have to be retaught in the second language.

Bilingual learners are able to pick up correct pronunciation quickly by learning the sounds of two languages something adults find difficult to do. Bilingual situation sometimes lead to ‘diffusion’ that is certain features spread from one language to the other as a result of the contact situation, particularly certain kinds of syntactic features. Wardhaugh, (2010:97).

A bilingual who learns that meaning can be represented in more than just one way that is through exposure to another language and thus another collection of sounds to represent the same objects has learnt something important about the nature of language and develops additional insights into the nature of language that are not available to the mono-lingual learner, Liddicoat, (2001:14-15). Much of the research on cognitive aspects of second language learning has focused on creative divergent thinking and many studies indicate a bilingual advantage in these areas Biahystok (2001) and Bialystok, et al (2005).

Bilinguals appear to develop a more analytical orientation to language due to their experience in organizing their two language systems and keeping them separate while they perform particular tasks. This experience appears to give them an advantage over mono-linguals when they perform tasks involving control of processing (Bailystock 2001).

Bialystok (2001) notes that bilinguals do not have a uniform or ‘across’ the board metalinguistic (relating the formal system of language to the other cultural systems or the study of language systems in distinction from that of paralanguage) or cognitive advantage of monolinguals. However, she suggests that early acquisition and regular use of two languages have been shown to enhance the ability of children to solve problems, which require them to selectively attend to information. For instance, where they are required to ignore or inhibit misleading information.

She refers to this as “control of linguistic processing” or “cognitive control” and detailed studies, which have shown this advantage for bilinguals over mono-linguals across several domains of thought, including concepts of quality spatial concepts and problem solving (Bailystok et al 2005:40).

Academic and cognitive skills transfer readily between language while there may be differences in the vocabulary, grammar and writing systems of languages, all languages with writing systems have in common that the reader must learn to make meaning from the text. Concepts and strategies involved in this, transfer easily from one language to another. The overall reading competence in two languages does not operate separately, Baker, (2006:330). Bilingualism has been shown to enhance children’s metalinguistic awareness and thereby their reading readiness. Bilingualism has cognitive advantages particularly in domains such as helping students understand the arbitrary nature of language systems.

Obviously, the major positive consequence of bilingualism is knowing two languages and thus being able to converse with a larger array of individuals, as well as having access to two cultures, two bodies of literature and two worldviews. Speaking other languages also has economic advantages as bilinguals are in high demand in the new global economy. There is also considerable evidence that many key literacy-related skills, including phonological awareness, print concepts, decoding skills and extended discourse are transferable from L1 to L2.

- THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF BILINGUALISM ON THE ENGLISH OF TERTIARY STUDENTS

The negative effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students are observed through the following features which include code-switching, code-mixing, interference of L1 on L2, code-borrowing, bilingualism and biculturalism.

1.8.2a. CODE-SWITCHING:

This is the interchangeable use of two languages within the same speech exchange by bilinguals in an informal setting, Osuafor (2002:199). Usually the participants in the speech situation share the same bilingual background and understand the syntactic structures of the language involved.

Code-switching is said to be operating where there is a conscious alternating of codes of different languages in the same communication setting usually at the inter-sentential or discourse level in order to impress, deceive or to disguise.

Akindele and Adegbite (1999:34) describe code switching as a means of communication, which involves a speaker alternating between one language and the other in communicating event. In other words, someone who code-switches uses two languages or dialects interchangeably in a single communication. This switching can be interlingual or intralingual. A communication which may involve a native tongue and a foreign language or two foreign languages or two dialects of a language can be initiated with one of the two languages and be concluded in the other for example, starting a discussion with Igbo and concluding in English.

Types of Code-Switching

Code-switching can be discussed from two different perspectives: that is Functional and Formal perspectives. The functional types of code-switching are the conversational, situational and metaphorical. In this perspective, the bilingual in an attempt to carrying out the communication employs items from two different languages and tie them together by syntactic and semantic relations.

Another characteristics of this code-switching is that participants often are not conscious of which language they are using at a point in time in their discussion. For instance, if Hausa and Igbo are switched in a conversation, the co-participants are not conscious of who switches from one language to the other and particular languages being used at a particular time. The speakers are mainly concerned with the message content of the conversation. Conversational code-switching is patterned much the same way as if it were following the grammatical rule for a single language. An understanding of the syntactic structures of the language involved is a necessary prerequisite for an individual to be able to codeswitch efficiently. Conversational code-switching is in vogue in everyday speech events particularly in informal situations.

In situatioinal code-switching, two different languages are assigned to two or more different situations. The setting, activity and participants in such situations remain the same. However, the two languages used in switching serve as a metaphor representing a different situation. This may be due to a change of subject matter or a new set of role relations.

The formal type of code-switching refers to the linguistic realization of code-switching from one language to the other. Code switching in this formal type refers to a complete change from one language ‘A’ to another language ‘B’. There is instead a blend of the two codes of communication involved in the communicative process. An inter-sentential code change realizes a switch that takes place across sentences e.g.

John was at the party, Onyere anyi mmanya, after that he introduced us to the celebrants. Obi toro ya uto. The intra-sentential code change or switch takes place within a sentence at major constituent boundaries such as noun phrases, verb phrases and clauses e.g. Ada wetaram cup ahu no n’elu table na palour. (Ada bring that cup on top of the table in the palour).

Reasons for Code-Switching

So many reasons abound why code-switching occurs in the speeches of individuals. It can occur when there is lack of facility in a language or by a speaker in discussing a topic in a language. It can also occur to serve a linguistic need of providing a lexical, phrasal or sentential filler in an utterance. Code-switching is used in quoting someone and also in qualifying (amplifying or emphasizing) parts of utterances. Speakers sometimes switch language to specify their involvement in communication or mark and emphasize group identity. They also switch to convey confidentiality, anger or annoyance and possibly to exclude someone or people from a conversation.

1.8.2b. CODE-MIXING

Code-mixing refers to a situation whereby two languages are used in a single sentence within major and minor constituent boundaries. The mixing of items occurs almost at word level. Akindele and Adegbite (1999:37).

Osuafor (2002:200) states that code-mixing is an informal speech setting which occurs unconsciously at the intra-sentential level. Code-mixing has also been defined by Kachru (1978:28) as “The use of one or more languages for consistent transfer of linguistic units from one language into another and by such a language mixture developing a new restricted or not restricted code of linguistic interaction.

The following examples from Igbo Bilinguals illustrates this phenomenon:

- Ngozi na-ata anu too much

Ngozi eats too much meat

- Kedu ka isi ere mango?

How do you sell mango?

- A agam enyeghachi gi ego ahu the moment I get it.

I will refund you that money the moment I get it.

- Ada ahu ga-eme ya affect permanently

That fall will affect him/her permanently.

- I saw the cup n’okpuru table.

I saw the cup under the table

Code-mixing therefore is more pronounced when the participants in speech situation are from the same bilingual background.

However, Akindele and Adegbite (1999:37) states that code-switching and code-mixing are so much inter-related in such a way that the later may trigger of the former and that it is very difficult to separate the two types. They also opine that the speaker who code-switches / mixes is not conscious of the fact that he is code-mixing or code-switching. They distinguish between situational and formal code-switching as well as among other sub-types like inter-sentential and intra-sentential code mixing.

1.8.2c. INTERFERENCE OF L1 ON L2

This refers to those instances of deviation from the norms of either language which occur in the speech of bilinguals as a result of their familiarity with more than one language (Akindele and Adegbite (1999:38), Opara S. C. (1999:18) defines interference as the trace left by someone’s native language upon the foreign language he has acquired or the influences of the mother tongue on the individual acquiring or learning a second or foreign language.

In other words, interference is a term, which refers to a situation whereby two different languages overlap. In such a situation, the linguistic systems of one of the languages are transferred into the other in the process of producing the latter, which is the second or the target language. For instance, English and Igbo, can be regarded as two different languages that overlap. In an attempt by an Igbo English bilingual to speak the language, the system of the Igbo language – grammar, lexis, phonology and semantics are transferred into those of English. In interference, one of the two or more languages in use in a speech community is dominant. The features of the dominant language are transferred to the subordinate or target languages at the phonological, lexical, and grammatical and discourse levels.

Two types of interference can be distinguished. The first type is the ‘proactive’ interference. This is an interference phenomenon that helps in the acquisition of the target language. This is called positive transfer or facilitation. The other type of interference is the ‘Retroactive’ type. This type retards the process of the acquisition of the target language. It is also called Negative transfer or interference.

There are many types of interference they include: Phonological interference, morphological interference, grammatical interference and semantic interference.

Phonological Interference

Some phonemes, which are present in the English language, are absent in our mother tongues. The Igbo language has eight vowel phonemes – /a, e, i, i, o, o, u, u/ whereas English language has twelve: /i: i, e, æ, a: :I⊃, ⊃: , u:, u, ⋀, Ʒ:, ∂/. English in addition to vowels has eight diphthongs (double vowel sounds) /ei, ai, ⊃i, ∂u, au, i∂, e∂, u∂/and three triphthongs (three vowel sounds: /ei∂, au∂, ai∂/.

Igbo language has no triphthong but unknown to many it has six diphthongs known as “Udamkpi”. They are /ia, ie, uo, io, uo, io/

Examples of these “udamkpi” diphthongs in words are:

ia as in ahia (market) bia (come)

ie as in rie (eat) ehihie (afternoon)

io as in diochi (palm wine taper)

io as in rio (ask) aririo (prayer/begging)

uo as in tigbuo (kill) tufuo (throw away)

uo as in abuo (two) puo (go)

Ofomata, C. (2002:223).

This problem of interference is further compounded by the fact that English vowels have been further divided into long and short vowels. The long vowels are:/i:, a:, u:, 3: ⊃: while the short vowels are: /ii, e, ae, ۸, l⊃, u, ∂. Consequently, Igbo speakers of English find it difficult to distinguish between the pronunciation of words such as sit, and seat, bad and bard, fist and feast.

The native language, Igbo also interferes with English in other areas for example, some Igbo speakers of English find it difficult to pronounce the letter ‘s’. They say ‘ch’ for ‘s’ for example miss becomes ‘mich’ others cannot distinguish between ‘l’ and ‘r’. they pronounce schoor for school. Certain letters are dropped and replaced by others, even within the same language, differences in dialects cause varying degrees of interference. For example, the uneducated man from Onitsha realizes the word ‘load’ /L∂ud/ as ‘road/ /r∂ud/, lorry/lori/as rorry/rori/ e.g. The rorry is lunning arong the load.

Areas of interference for Yoruba speakers are also predicted here. He will encounter problems in the production of sounds that are not present in Yoruba but are present in English sound system, as in these consonant sounds.

/θ, ð/ /t/ for example, ti k/ for / θiŋk/ ‘think’

/p/ /khp/ for example, /khpik/ for /pik/ ‘pick’.

/z/ /s/ for example, siŋk/ for /ziŋk/ ‘zinc’

/v/ /f/ for example, /feri/ for /veri/ ‘very’

The sounds /θ/ and /ð/ which are not present in the Yoruba alphabet are realized as /t/, /p/ is pronounced as /khp/.

/z/ as /s/ and /v/ as /f/. Consonant clusters like /ch/, /t∫/ in words like ‘chicken’, change and chin-chin are pronounced as ‘sikini’, ‘sendz’ and ‘sin-sin’.

Oyeleye (1996:22) remarks that the sound /٨/ appears a particularly difficult sound for most Nigerians who tend to use a half open vowel namely /o/ sound for English /٨/ as found in words like but, cut, hut, must etc. /∂/ (schwa sound) is another difficult sound to pronounce. It is a long weak vowel found in words like above, away etc.

Researchers on sound discrimination based on observation revealed that this pattern of pronunciation runs across other native languages in Nigeria as shown below.

Words (English) Words (Hausa)

Very /feri/ for /veri/

Plenty /flenti/ for /plenti/

Pure /fju∂r/ for /pju∂r/

Federal /pedrl/ for /fedr∂l/

Words (English) Words (Calabar)

Goat coat/k∂ut/ for /g∂ult

Love rove/rov/ for /L٨v/

Naira naila/nil∂/ for /nairæ/

Champion jampion/jampjon/ for /t∫æmpi∂n/

Jacket yacket/jæket/ for /d3ækit/

Indigenous languages do not have certain English vowels which they substitute with vowels in their mother-tongues that are fairly close to them. Example of such vowels are:

/∂e/ as in man, catch Nigerians pronounce.

/a:/ as in far, arm these two sounds as /ą/

/٨/ as in cut, love Nigerians pronounce

/3:/ as in nurse, word the two sounds as /lכ/

/∂/ as in ∂way, above Nigerian pronounce

this sound as /a/

/ei/ as in gate, eight pronounced as /e/

/∂u/ as in goat, go pronounced as /o/.

Examples of Consonants that are usually substituted or omitted by some Nigerian /Igbo bilinguals include:

/θ/ as in ‘think’, ‘both’ which is pronounced as /t/.

/ð/ as in ‘that’, ‘father’ pronounced as /d/.

/h/ as in ‘house’, ‘behind’ which is omitted completely by some Yoruba speakers e.g. pronounced as ‘ouse’.

/t∫/ as in ‘church’, ‘charge’, which is pronounced by some Nigerian speakers as /∫/.

/Ʒ/ as in ‘treasure’, ‘measure’ pronounced as /j/ and sometimes /s/.

Insertion of vowels where there are consonant clusters in English. This is because, the syllable structure of Nigerian language is usually CV (consonant followed by a vowel, CVCV-(Consonant + vowel + consonant + vowel) or VC V (Vowel + consonant + vowel) and VCVCV (vowel + Consonant + vowel + consonant + vowel).

For example:

CV – gi – you

CVCV – Bata – come in.

VCV – aka – hand

VCVCV – akuku – side.

Whereas the English syllable structure can accommodate as many as three consonants before a vowel and four consonants after a vowel (C 0-3) V (C 0-4). Uzoma I. Nwachukwu (2007:40).

This interference results in mispronunciation of such words as:

Stream / stri:m/ pronounced by Nigeria bilinguals as / sitirim/

Breathed / bri: ðd/ pronounces as /birited/.

Bread /bred/ pronounced as / bered / clothed /klauðd/ pronounced as /kuloted/.

The use of wrong stress, rhythm and intonation as a result of different speech systems. English word – stress consist of strong and weak stress whereas Nigerian language are tonal consisting of high, low and mid or level tones which are used to distinguish word meaning. For example in Igbo language we have:

Oke – HH – male

Oke – LH – rat

Oke – LL – share

Oke – HL – boundary.

The problem Nigerians have with English word stress is that it is not always predictable for example, the word ‘export’ can be stressed on the first syllable when it is a noun (export) and on the second syllable when it is a verb (export), but it will be risky to generalize. For example, the word ‘comfort’ is stressed on the first syllable as a noun and also as a verb. Similarly, the word ‘cement’ is stressed on the second syllable (cement) both as a noun and as a verb.

With respect to rhythm, English sentences are stress-timed whereas our indigenous languages are syllable-timed. Being stress-timed means that in English speech, there is a tendency to move from one stressed syllable to another at regular interval of time. This makes English speech relatively faster than our indigenous languages that are syllable – timed.

Furthermore, English is an intonational language in which the speaker tends to move from one phrase to another rather than moving from one word to another which slows down speech.

Intonation in English has a system in which there are characteristic intonation patterns. For example, statements and commands are said with the falling tone whereas polar – questions are said with the rising tone as:

(i) Mary is a student (statement)

(ii) Sit down (command)

(iii) Are you a student? (Polar-question)

The general tendency is that Nigerians speak English the way they speak their mother tongues.

Grammatical Interference

At the grammatical level, lack of correspondence between systems (such as article, pronoun, tense, concord, etc) is the main source of interference.

(i) Article omission: Nigerian languages do not have the articles system which gives rise to such ungrammatical sentences as:

“I have problem” (instead of I have a problem”)

“She killed snake” (instead of she killed a / the snake”)

(ii) Non-separation of gender: In Igbo, for example, there is no gender distinction in the use of a pronoun.

For example:

O na-eri ihe (he/she is eating).

The above sentence is the reason for such common grammatical mistakes among Nigerians as in this sentence below.

“Mary is my sister, He is a doctor”.

Semantic or lexical interference

At the semantic or lexical level, interference occurs mainly as a result of transliteration in which learners first think in their native languages and try to translate their first language idioms into English. This gives rise to such expressions as the following:

- I am coming (meaning- I’ll shortly be back).

- We don’t hear English (meaning-we don’t understand English)

- Come now now (meaning-come immediately)

- Are you not hearing the smell? (meaning “don’t you perceive the odour?”)

- I’m seeing you (meaning- I can see you)

Nwachukwu U.I. (2007:43)

Lexical interference can further be described under five categories identified below (Akindele and Adegbite (1999-41-43)

Semantic Contrast

Some items in Nigerian English (NE) may have equivalent items in native English but express different meanings through them for example, the item “Masquerade” has to do with ancestral cult worship in Nigerian English but it means ‘deceit’ or hiding one’s identity in Native English.

Semantic Extension

Some items in Nigerian English may have equivalence in native English but express a wider meaning in Nigerian English for example, chief, brother, father and mother. In addition to its meaning in Native English, ‘chief’ in N.E. is a social title awarded to important personalities. Also ‘father’ does not refer to a male parent alone but any adult male person of comparable age to one’s father.

Semantic Transfer

Some items in Nigerian English (NE) are present in native English but the concepts they express in the former are absent in the later.

For example:

Obi’s wives (suggesting polygamy) and

Bride price meaning (dowry paid by bride’s parents)

In mixed transfer, items partly from the mother tongue and partly from English are conjugated or collocated for example ‘bukateria’ (buka in Yoruba means ‘canteen’) while ‘teria’ is clipped from English ‘cafeteria’. Kiakia bus refers to a fast-moving bus or minibus.

Gwongworo bus (big bus in Igbo English)

Outright transfer can be observed in loaning or borrowing of items, for example, Eba, Obi, Alhaji, Walahitalahi..fa. In loan translation, mother tongue word is reproduced directly e.g. water has gone again, open the tap, tight friend, good talk, afternoon meal etc.

Coinages (Loan Creation): Some items are peculiar to Nigerian English but denotes N.E. experiences which are also present in native English for example: long-leg (nepotism) go-slow (traffic jam), been-to (someone who has been to overseas), cash madam (wealthy woman), to spray money (spend extravangtly or less lavishly) sugar daddy/mummy (a much older male or female lover).

Discourse Interference

This is more pronounced at the level of greetings. For instance, the system of greetings in Igbo differs from that of English. An Igbo-English bilingual transfers the system of greetings in Igbo to English. Igbo people like the Hausa or Yoruba have greetings for every human endeavour.

For example:

Appreciation Interference equivalent

A: I meela/Ndewo A: Thank you

B: Daalu B: Thank you

For bereavement

A: Ndo, karaobi/oma Accept my sympathy

B: O! imeela/daalu Yes thank you

At work

Jisike/Daalu oru Weldone

To welcome somebody

A: Nnoo/I biala You are welcome

B: O! daalu Thank you

The system of greetings is also observed through the production of lengthy greetings in place of casual greetings which characterize the English discourse, that is, in place of “Hello/Hello”, the Igbo-English bilingual goes further to say “How are you?”, “How is your family?”, “How are your children?” etc.

Example:

Igbo Greetings Interference Igbo-English

A: Deede, I boola chi A: brother good morning

B: Kedu ka unu di? B: How are you?

B: O/Anyi di nma B: I/We are fine

A: Ole otu ezi na ulo di? A: How is the family?

B: Anyi di nma A: We are fine/alright

A: Ole otu umuaka gi di? A: How are your children?

B: Ha dicha nma B: They are all fine

A: Kelerem ha nile B: Greet all of them for me

B: Gaa nke oma B: Good-bye

1.8.2d. CODE BORROWING

Borrowing can be defined as the occasional use of items from one language in utterances of another language (Akindele and Adegbite, 1999:43). This arises out of the fact that there is no language in the world that can be regarded as self-sufficient and as such every language borrows from another.

Borrowing cannot be regarded as a feature of bilingualism or multilingualism alone, it is also a feature of monolingualism. In monolingual speech in English, we have such lexical items as ‘resume’, ‘elite’ which are borrowed into English. In the Nigerian context, each of the indigenous languages borrowed from one another e.g. the words ‘wahala’, and ‘seria’ are borrowed from Hausa into Yoruba.

In terms of the English language, several English words have been borrowed into the indigenous languages for instance, in the Igbo language such words as redio (radio), windo (window), pilo (pillow), tebulu (table), moto (motor), kopu (cup) etc. Also, some Igbo items feature in the English of Igbo-English bilinguals for example: Ogiri (native seasoning), ochu (committing a kind of offence that the land abhors), ukwa (a kind of food), ogbunigwe (war weapon) etc.

1.8.2.e BILINGUALISM-BICULTURALISM

It has already been said that language reflects, expresses and records culture. The possession of a language inevitably means the acquisition of a culture. However, while we can say that a monolingual person is essentially monocultural not all bilinguals can be said to be bicultural (except a coordinate bilingual) since bilingualism and biculturalism are not co-extensive) (Cf Haugen, 1956) in Akindele and Adegbite, 1999:44).

Indeed, a monolingual person may be bicultural in some circumstances for example, some second or third generation immigrants with two cultures in the U.S.A. The extent of bilingualism may determine extent of biculturalism, but not always. Relationship between the extent of bilingualism and biculturalism can be demonstrated in four ways of the High (H), Low (L), scales. Thus H-H, H-L, and L-L.

Cultures like language come in contact too. For example, an immigrant may experience “culture shock” as he encounters differences in a new culture as eating habits, courting behaviuor, child rearing, family, organization, religious beliefs etc. However, the immigrant will get out of this shock after he has undergone the process of acculturation in the new environment.

A speakers’ purpose of learning a second language can determine his acquisition of the second language. If he aims at identification and assimilation, he becomes both bilingual and bicultural; but biculturalism may end up being transitional towards monoculturalism in the second language. Also children and youths who are bicultural may rebel against the language and culture of their parents in an attempt to show civilization.

Therefore, it is the persistent decline in the proficiency of the English of tertiary students in a bilingual or multilingual situation that prompted the background of this study.

- STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

An important feature of bilingualism is that it is a consequence of language in contact which deals with the direct and indirect influence of one language on the other.

The imposition of English language in Nigeria by the colonial masters institutionalized bilingualism. English language functions as official language and a lingua franca in Nigeria and is learnt as a second language (L2) among other indigenous languages yet the level of proficiency is still below standard. This problem is of great concern to the linguists and researchers. This research is therefore an attempt to investigate the effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students.

- PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

In view of the fact that Bilingualism is the use of the two languages by an individual or a speech community, the researcher wants to investigate the effects Bilingualism has on the English of tertiary students learning English language both positively and negatively and also to proffer solutions that will help in achieving proficiency in the language.

- SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

This study is set to investigate the effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students. It is believed that the researcher findings will:

- expose the learners of English language to areas of difficulty or interference which hinders the achievement of proficiency in the language and possibly proffer solutions to these problems.

- aid English language teachers to lay emphasis on areas of difficulty and drill the learners on the correct forms.

- create awareness to the learners, teachers, society and the users of the language.

- enlighten the syllabus designers, text book writers and curriculum planners on more areas of emphasis in order to ameliorate the negative effects

- also enlighten the government on deploying qualified and competent teachers in the teaching of the language.

- RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This research is designed to find answers to the following questions:

- Does bilingualism aid the learning of English of tertiary students?

- Does code-switching and code-mixing affect the English of tertiary students?

- How does mother tongue (MT or L1) interfere with the acquisition of proficiency in the learning of English of tertiary students?

- Does code-borrowing affect English language learning?

- Does culture affect tertiary students’ English?

- DELIMITATION OF THE STUDY

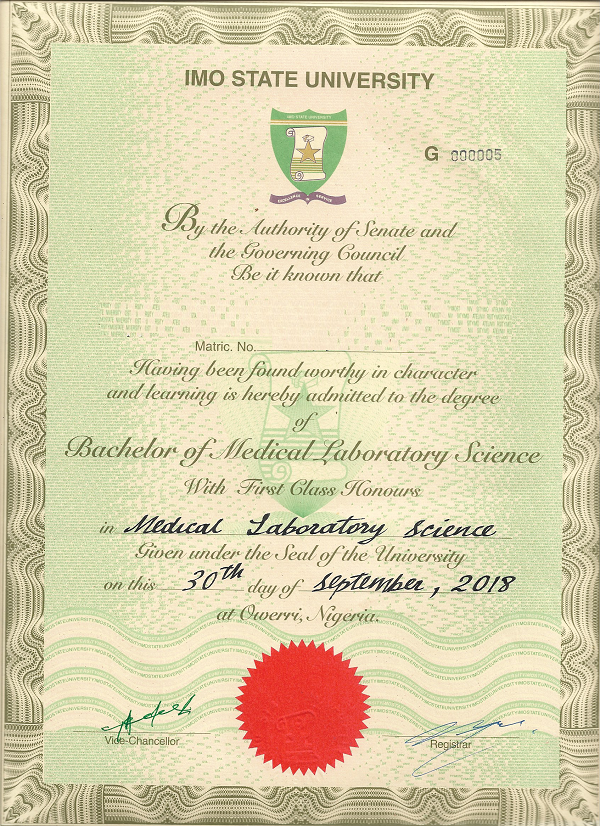

This is delimited to the study of the effects of Bilingualism on the English of tertiary students. The emphasis is on the positive and negative effects of bilingualism on the English of tertiary students. The population of the study is made up of students from the Department of English and Literary Studies, Imo State University and Department of English Language Studies, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri.

- LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

This study is carried out through the administration and collection of questionnaire by the researcher. Due to time and financial constraints, the study will be restricted to two tertiary institutions.

Pages: 171

Category: Project

Format: Word & PDF

Chapters: 1-5

Material contains Table of Content, Abstract and References.

You may like

Project Materials

IMSU Info contains over 1000 project material in various departments, kindly select your department below to uncover all the topics/materials therein.

Project Topic Search

- Accountancy 6

- Adult & Non-Formal Education 1

- Agric. Economics & Extension 7

- Anatomy 1

- Animal & Environmental Biology 10

- Architecture 2

- Arts & Design Technology 1

- Arts & Social Science Education 2

- ASUU Strike 17

- Banking & Finance 6

- Biochemistry 8

- Biology 1

- Building 3

- Business & Loans 17

- Business Administration 6

- Business Education 17

- Business Law 1

- Chemistry/Industrial Chemistry 5

- Civil Engineering 3

- Computer Education 4

- Computer Science 5

- Curriculum and Instructional Technology 3

- Development Studies 2

- Economics 16

- Education 32

- Education Accountancy 45

- Education Administration 1

- Education Agriculture 12

- Education Biology 25

- Education Chemistry 2

- Education Economics 33

- Education English 10

- Education Government 16

- Education History 2

- Education Mathematics 9

- Education Physics 2

- Education Religion 1

- Educational Foundations 11

- Educational Psychology 1

- Electrical & Electronic Engineering 5

- English & Literary Studies 11

- Environmental & Applied Biology 2

- Environmental Science 5

- Environmental Technology 1

- Estate Management 7

- Fine and Applied Arts 2

- Food Science & Technology 9

- Foundations & Counselling 1

- French 1

- FUTO News 3

- Gender & Development Studies 1

- Geography & Environmental Management 2

- Government & Public Administration 6

- Guidance & counseling 6

- History & International Studies 8

- Hospitality & Tourism Management 47

- Human Physiology 1

- Human Resource Management 1

- IMSU News 220

- Industrial Technical Education 1

- Insurance & Actuarial Science 15

- Integrated Science 1

- JAMB News 29

- Language Education 6

- Law 2

- Library & Information Science 29

- Life Science Education 9

- Linguistics and Igbo 2

- Management Studies 6

- Marketing 2

- Mass Communication 14

- Mechanical Engineering 3

- Medical Laboratory Science 18

- Microbiology & Industrial Microbiology 4

- Nursing Science 10

- Nutrition & Dietetics 27

- NYSC News 18

- Office and Technology Management Education 9

- Opportunity 25

- Optometry 10

- Others 45

- Physics/Industrial Physics 6

- Political Science 12

- Primary Education 25

- Project Management Technology 1

- Psychology 7

- Psychology & Counselling 2

- Public Administration 2

- Public Health 6

- Quantity Surveying 2

- Radiology 1

- Religious Studies 11

- Scholarship 29

- School News 44

- Science & Vocational Education 1

- Science Education 4

- Social Science Education 36

- Sociology 10

- Sociology of Education 1

- Soil Science & Environment 3

- Sponsored 3

- Statistics 1

- Surveying & Geoinformatics 2

- Theatre Arts 3

- Theology 1

- Urban & Regional Planning 7

- Veterinary 2

- Vocational and Technical Education 8

- Vocational Education 76

- WAEC News 2

- Zoology 6

Is It Worth Registering a Pre-degree Program In IMSU? All you need to know about IMSU Pre-degree

7 Popular department in Imo State University (IMSU)

IMSU reprinting for 2023/2024 post UTME candidates has commenced

Steps on How to Apply for Certificate in Imo State University, Owerri (IMSU)

Is It Worth Registering a Pre-degree Program In IMSU? All you need to know about IMSU Pre-degree

7 Popular department in Imo State University (IMSU)

IMSU reprinting for 2023/2024 post UTME candidates has commenced

Steps on How to Apply for Certificate in Imo State University, Owerri (IMSU)

Is It Worth Registering a Pre-degree Program In IMSU? All you need to know about IMSU Pre-degree

7 Popular department in Imo State University (IMSU)

IMSU reprinting for 2023/2024 post UTME candidates has commenced

Steps on How to Apply for Certificate in Imo State University, Owerri (IMSU)

Trending

-

IMSU News4 years ago

IMSU News4 years agoIs It Worth Registering a Pre-degree Program In IMSU? All you need to know about IMSU Pre-degree

-

IMSU News4 years ago

IMSU News4 years ago7 Popular department in Imo State University (IMSU)

-

IMSU News2 years ago

IMSU News2 years agoIMSU reprinting for 2023/2024 post UTME candidates has commenced

-

IMSU News3 years ago

IMSU News3 years agoSteps on How to Apply for Certificate in Imo State University, Owerri (IMSU)